Coffee and Italy is a match made in heaven. After all, where would we all be today without its offspring – the reenergising and fragrant espresso?!

While coffee is drunk all over the world, Italy – for more than 400 years – is at the forefront of establishing the gold standards in terms of how it should be properly made and taken.

The words espresso and cappuccino have become part of a universal vocabulary shared by people everywhere. Italian coffee-making machines gleam in every self-respecting coffee house from Canada’s Vancouver to Australia’s Wagga Wagga. Italian coffee culture has inspired the creation and the non-stop growth of large multinational coffee shop chains.

Yet, to this day, there are still many sides of the authentically Italian coffee heritage which remain hidden or little-known unless you decide to seriously delve into it.

In case you are interested to learn more about coffee in Italy and how a rich set of traditions grew around it, here are 101 facts about Italian coffee culture.

Organised in logical and simple chunks, they will give you an exhaustive overview of how this intensely dark and aromatic drink first reached Italy and then quickly gained a foothold here eventually becoming synonymous with the country itself. From famous Italians who shaped the world’s coffee culture to coffee in Italian cuisine and art, from mentions of coffee in Italy’s written works to a list of Italy’s oldest coffee houses and a handy Italian coffee glossary, everything is covered.

Behind this blog post are my five years spent here in the north of Italy constantly engaged in the acts of drinking coffee, visiting historical coffee houses, exploring coffee museums, talking to and reading about people who take coffee seriously. I had a lot of fun researching and writing all this information while keeping my energy up and my focus on with countless cups of coffee. Some of which were photographed and you will see them featured here!

I hope that these 101 facts about coffee in Italy and Italian coffee culture will give you lots of fascinating information to muse on next time that you are enjoying a precious coffee moment.

For, as the renowned Italian composer, Giuseppe Verdi once said: Il caffe’ e’ il balsamo del cuore e dello spirito!

Indeed, coffee is balm for the heart and the spirit.

Now, let’s sip in!

Coffee in Italy or 101 Facts about Italian Coffee Culture

Coffee in Italy – A Historical Overview

While it is thought that coffee first reached Europe during the 16th-century sieges of Vienna and Malta by the Ottoman Turks, the first Europeans to officially trade with coffee as consumer goods were the enterprising merchants of the Republic of Venice.

In the second half of the 16th century, letters and reports mentioning coffee and written by ambassadors, physicians, and travellers from the Italian city-states had started to arrive from Constantinople, Cairo and other large cities of the Muslim world. In them, they described the custom of drinking kahve – a strong black liquid made of beans which, allegedly, could keep a man awake.

Relying on their strong trading contacts across the Orient, Venetian merchants started to import coffee beans alongside their usual loads of species, silk, and perfumes. Originally, coffee was sold for extortionate prices in the pharmacies as a remedy for the digestive tract.

Local wine sellers soon felt threatened by coffee’s increasing popularity among the students and professors of Padua University – at the time an important intellectual hub in Venice’s mainland territories. In addition, coffee was met with the disproval of zealous church-goers in the Catholic city-states. Seeing that it came from the Arab lands, priests called it ‘Satan’s drink’ and insisted that it couldn’t have anything to do with the Christian life.

In 1600, an appeal was made to Pope Clement VIII to banish coffee. The Pope, after sampling a cup of the fragrant new drink offered to him by a Venetian merchant, found it to be delicious and invigorating. Hence he sanctified coffee in order to banish the devil from it and allow its use. Considering that Clement VIII was the Pope who sent Giordano Bruno to the stake, it is quite a miracle, really, that he had such a progressive attitude to coffee.

Soon appetite for the aromatic drink grew and in 1624 the first significant load of coffee arrived by boat in Venice. In a few short decades, the Italian word caffe’ was coined and the new fashion of drinking coffee took over Venice and the rest of Italy parallel with Europe herself.

From the middle of the 17th century, coffee was sold in Italy by ambulant sellers who also offered hot chocolate, lemonade, and liquors from their stalls.

Then the bottega del caffe’ – the prototype of the modern coffee shop – came on stage. Although it is widely thought that the first Italian coffee house opened in 1645, the first reliable documents cite 1683 when a coffee house opened at St. Mark’s Square in Venice. Coffee houses proliferated to the point that on 4th October 1759 a law was passed in Venice stating that their number couldn’t exceed 206. Yet, by 1763, there were 218 coffee shops in Venice. Friends, lovers, aristocrats, and tradesmen would congregate in them. Buying a lady a cup of coffee and having it sent to her table was a way to express one’s love and devotion to her.

Meanwhile, in 1686 in Paris, France the Sicilian chef Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli opened a cafe – Le Procope. To this day it remains Paris’ oldest cafe in continuous operation. It counted Voltaire and Diderot among its patrons.

Back to Italy, where in 1715 a coffee plant was received for the first time at Pisa University’s Botanical Garden. One of the oldest botanical gardens in the world, at the time it was flourishing under the patronage of Cosimo III di Medici – the enlighted ruler of Florence. Michelangelo Tilli – physician, member of the Royal Society, and director of Pisa University’s Botanical Garden – was first to come up with the idea to use hothouses in order to acclimatise and grow coffee plants in Italy and Europe.

It’s interesting to note here that the immediate and ever-increasing popularity of coffee in Italy and the rest of Europe from the 16th-17th centuries onwards was helped by three significant factors:

- Nature – From roughly 1600 to 1850, a period of very cold summers and freezing winters plagued the continent. It came to be known as the Little Ice Age and it caused crop failures, famines, and in some cases population decline. For example, in 1709, 1789, and 1791 the lagoon and all canals in Venice froze over. Coffee warmed up the body and kept the spirits high. It also made you feel full when nothing else was on the table.

- Industrial Advances – with the discovery of the pendulum by Galileo Galilei in 1583 and, consequently, the ability to make clocks, the rhythm of daily life sped up. From working the fields or in small workshops, large groups of people were redirected to labouring in the newly set-up industrial enterprises. Coffee helped them deal with the lack of natural light and shift work in enclosed spaces.

- Fight against Alcoholism – In an era when water was often contaminated and unsafe to drink, people would consume large quantities of beer and wine to keep hydrated. With the rapid industrialisation, turning to work hangover brought with it significant safety risks. Coffee was a better alternative to keep awake and alert without losing control.

Coffee also appealed to the artists and intellectuals of the time. Coffee houses became places where they would congregate to exchange ideas and discuss the matters of the day.

In 1884 a steam-powered coffee-making machine was invented by Angelo Moriondo from Turin. It optimised the extraction of coffee thus making it possible to prepare and serve coffee in record times. However, Moriondi’s machine brewed coffee in bulk rather than extracting an individual cup of espresso for each customer. Plus, the inventor never mass-produced his design, preferring to simply use a few carefully built machines in his family’s coffee houses in Turin.

In 1901, the engineer Luigi Bezzera from Milan patented the first proper bar coffee machine. With it, espresso firmly stepped on the world’s coffee stage, swiftly conquering it.

In 1905, Pier Teresio Arduino created the iconic Victoria Arduino – an espresso machine that looked like a pillar and was made of copper and brass. In keeping with the Liberty style that was all the rage in Italy at the time, the Victoria Arduino machines were ornamented with eagles, angels, and winged victories. For almost 50 years, countless Victoria Arduinos proudly presided over thousands of Italian bars.

The first horizontal bar espresso machines would be invented only in the 1940’s. The most famous one of them was La Cornuta by the designer Gio Ponti who took inspiration from the sleek forms of the American jukebox and fast cars.

Meanwhile, at home, Italians started using a Moka Express to make their morning coffee and also to serve freshly prepared coffee to their guests. The Moka Express coffee pot (known simply as Moka) was invented by Angelo Bialetti and patented by him in 1933. Widely used to this day, the Moka works thanks to the pressure of vapour (about 1 atmosphere) which pushes the water from the bottom half of the pot up through the ground coffee in its middle and into the top half.

Nowadays, Italy is one of the world’s largest coffee roasters. Triest and Genoa in the north of the country are two of the main ports where coffee arrives in Europe. Several large coffee companies like Lavazza, Segafreddo, Hausbrandt, and Illy dictate coffee fashions and blends for millions of coffee aficionados. Plus, Northern Italy has its own coffee chain – Dersut – with dozens of coffee shops in many cities and towns.

Coffee in Italy’s Written Works

Italy’s deeply running coffee traditions are reflected in the body of written works created and published here over the centuries. From botanical descriptions of the coffee plant and cultural observations on the coffee houses of Cairo and Constantinople to mentions of coffee and its history in several literary works, a fragrant cup of coffee is never far away for Italian writers.

Here is a short list of some of the most important references to coffee in Italy’s written works. Where possible, I have provided a link to the respective text in its original so that you can have a look:

Gianfrancesco Morosini – an ambassador of the Republic of Venice – provided one of the first descriptions of Constantinople’s coffee houses to reach Europe. In a report to the Venetian Senate in 1585, Morosini sternly accused the locals of wasting a large amount of their time to leisure. He described them as drinking in public, in the shops or on the streets a black liquid, as hot as they could take it. This liquid was obtained from beans called cavee to which the locals ascribed the property of keeping a man awake.

If you are curious, here are Morosini’s exact words in Italian: la maggior parte dissipa il suo tempo nell’ozio. Per tutto il tempo se ne stanno seduti e per svagarsi usano bere in pubblico, nei negozi o sulle strade, un liquido nero, caldo quanto possono sopportarlo, che e ricavato da un seme che essi chiamano cavee […] gli si attribuisce la proprieta di tenere sveglio un uomo.

In 1592, the physician and botanist Prospero Alpini published in Venice his book on Egyptian plants De Plantis Aegypti liber. In it, the Arabica coffee plant took pride of place. Alpini was the first European to scientifically describe it and to provide detailed drawings of the plant and its seeds. He even included information about its pollination. Originally from the small town of Marostica (then part of the Republic of Venice), Alpini had spent three years in Egypt as the doctor of the Venetian consul. Quite importantly, he established that the Arabica coffee plant is autogamous, i.e. able to reproduce autonomously. Alpini called coffee caova based on the word in use in Egypt at the time. He also extolled its revitalising powers and listed its medical and pharmacological properties in his book

The first testimony of the Turkish word for coffee – kahve – in Italy is in the writings of the composer, musicologist, and explorer Pietro della Valle. Between 1614 and 1626, he travelled across Turkey, Egypt, Eritrea, Palestina, Persia, and India. In his Viaggi (1614-1615), a travel book written in Italian, della Valle enthused about coffee as an energising drink. Using the word kahve heard in Turkey, he also explained the rituals around coffee and the proceedings of making it.

Della Valle also developed the improbable thesis that the anti-sorrow drug which Helen of Troy mixes with wine in the fourth book of Odyssey had been nothing else but coffee (other writers and researchers, actually, point to opium instead).

In 1671, an Italian newspaper published in extracts one of the first treatises dedicated to coffee. Called De Saluberrima Potione Cahue, Seu Cafe Noncupata Discursus, it was written in Latin by the Maronite friar Antoine Faustus Nairon who had become a Professor of Oriental Languages in Rome.

In his treatise, Nairon lauded coffee’s wholesome virtues. Most interestingly though, Nairon was the first to tell the famous story of the Ethiopian goat herder Kaldi. Although it is nowadays considered to be apocryphal as it can’t be found in any Arabic sources, this is the widely-known story of how coffee was first discovered by humans. Here it is in a nutshell:

One night the goats didn’t return from pasture. Kaldi, very worried, went looking for them. He found them in the morning, dancing close to a green bush covered with lustrous red cherries. Kaldi, curious, tasted the cherries and thus discovered coffee’s stimulating properties. He took a long trip to the Chehodet Monastery in Yemen in order to show the bush’s fruits to the monks.

One of the monks there declared the stimulating fruit to be the ‘Work of the devil!’ and he threw the cherries in the fire. They released a rich, tempting aroma. The beans were immediately collected, crushed and soaked in a jug with cold water. This was the first cup of coffee in the world. The drink – bitter and dark – allowed the monks to remain alert during the long nights of prayer.

The word about the new drink soon spread from one monastery to another and coffee began to be considered a real gift from God. From there, coffee spread across the Islamic cities to then reach Europe via Venice first.

In 1685, the Italian scholar and natural scientist Luigi Fernando Marsili published in Vienna his work Bevanda Asiatica (Asian Drink) with the subtitle Trattatello sul Caffe’ (A Pamphlet on Coffee). Marsili described the coffee plant and gave detailed instructions on how to prepare a strong Turkish coffee.

The first use of the Italian word caffe’ (meaning coffee) in Italian literary works is registered in the dithyramb Bacchus in Tuscany by Francesco Redi. Curiously enough, Redi was an Italian physician, naturalist, and biologist. Lauded as the Father of Modern Parasitology, Redi was also a poet!

In his dithyramb, which Redi began to write in 1666 and published in its entirety in 1685, he exalts wine and, among many other things, he says: beverei prima il veleno, che un bicchier che fosse pieno dell’amaro e reo caffè. Which translates as: ‘I’d rather drink poison than a cup full of bitter and evil coffee.’ Strong words, indeed!

In 1731, Giovan Domenico Civinini – a physician from the Tuscan city of Pistoia – gave a lecture on the story and nature of coffee in front of the Botanical Academy of Florence. Civinini described the origins and the properties of coffee. He also recounted the different discoveries and studies done on coffee until that moment. Later that year, his speech was published as a book by the Florentine publishing house Stamperia Paperini under the name Della storia e natura dell caffe.

The renowned Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni mentioned coffee in a couple of his works. In 1750 he wrote one of his most important plays La Bottega del Caffe’. The comedy takes place from sunrise to sunset in a Venetian coffee house – a meeting point of sins and virtues where the destinies of personalities from different Italian cities intersect. A famous line from this play is: Una volta correva l’acquavite, e adesso e’ in voga il caffe’ (Brandy used to be in, and now coffee is in vogue).

In 1753, Goldoni wrote his tragicomedy La Sposa Persiana (The Persian Wife). A notable moment in it is when Curcuma, while she serves a cup of coffee to Ali, describes in a few verses how coffee is grown, where it comes from as well as the right steps to make a good cup of coffee. For example, she remarks that coffee grows in fertile soil and that it needs shade and not too much sun. Curcuma then says that coffee needs to be used freshly ground and that it needs to be zealously kept in a warm and dry place.

Famous Italians who Shaped Contemporary Coffee Culture

They say that behind every great cup of coffee there is a great man!

As such, here are some of the people whose inventions over the last century or so have shaped Italian coffee culture and the world’s appreciation for it.

Angelo Moriondo (1851-1914) – the inventor of the steam-operated coffee-making machine. It was patented first in Italy on 16th May 1884 and then internationally on 23rd October 1885. The title of his patent was Nuovi apparecchi a vapore per la confezione economica ed istantanea del caffe in bevanda, sistema A. Moriondo (in English: New steam machinery for the economic and instantaneous confection of coffee beverage, method A. Moriondo). It’s important to note that Moriondo never had his design mass produced. He was content to have a few hand-built machines in his family’s cafes in Turin.

Luigi Lavazza (1859-1949) – founded the Lavazza company in 1895 in Turin, Northern Italy. One of the world’s most famous coffee brands, to this day Lavazza stands out with its bold advertising campaigns. Some of its most memorable slogans in Italy are:

- Il caffe’ e’ un piacere; se non e’ buono, che piacere e’? – which in English means: Coffee is a pleasure. If it’s not good, what pleasure is it?

- Caffe’ Lavazza, piu’ lo mandi giu’ e piu’ ti tira su’. – which in English can be translated more or less as: Lavazza Coffee, the more you get it down, the more it brings you up.

Luigi Bezzera – an engineer from Milan, in 1901 Bezzera patented several improvements of the original steam coffee machine, thus creating in the process the first true bar coffee machine. His machine was able to make about a hundred cups of espresso coffee a day.

Desiderio Pavoni – bought Bezzera’s patent in 1905 and started producing espresso machines under the brand name La Pavoni.

Alfonso Bialetti (1888-1970) – inventor of the Moka Express coffee pot beloved by all Italians. Bialetti patented the Moka Express in 1933 thus making it possible for Italians to prepare cheaply and easily fresh espresso at home as and when they wanted. Made of aluminium, the Moka Express pot was very light and easy to use which helped it become incredibly popular all over Italy. To this day, a Moka pot can be found in every Italian household. They say that over 330 million Moka pots have been produced by the Bialetti company since the product’s first inception. Shops all over Italy sell Moka pots in any possible size alongside dozens of different blends and brands of coffee specifically ground to be used in a Moka pot. You will recognise a Moka pot by its iconic octagonal design and also by its mascot – a caricature of a mustached man with his arm lifted up and a finger pointing up as if asking for yet another espresso.

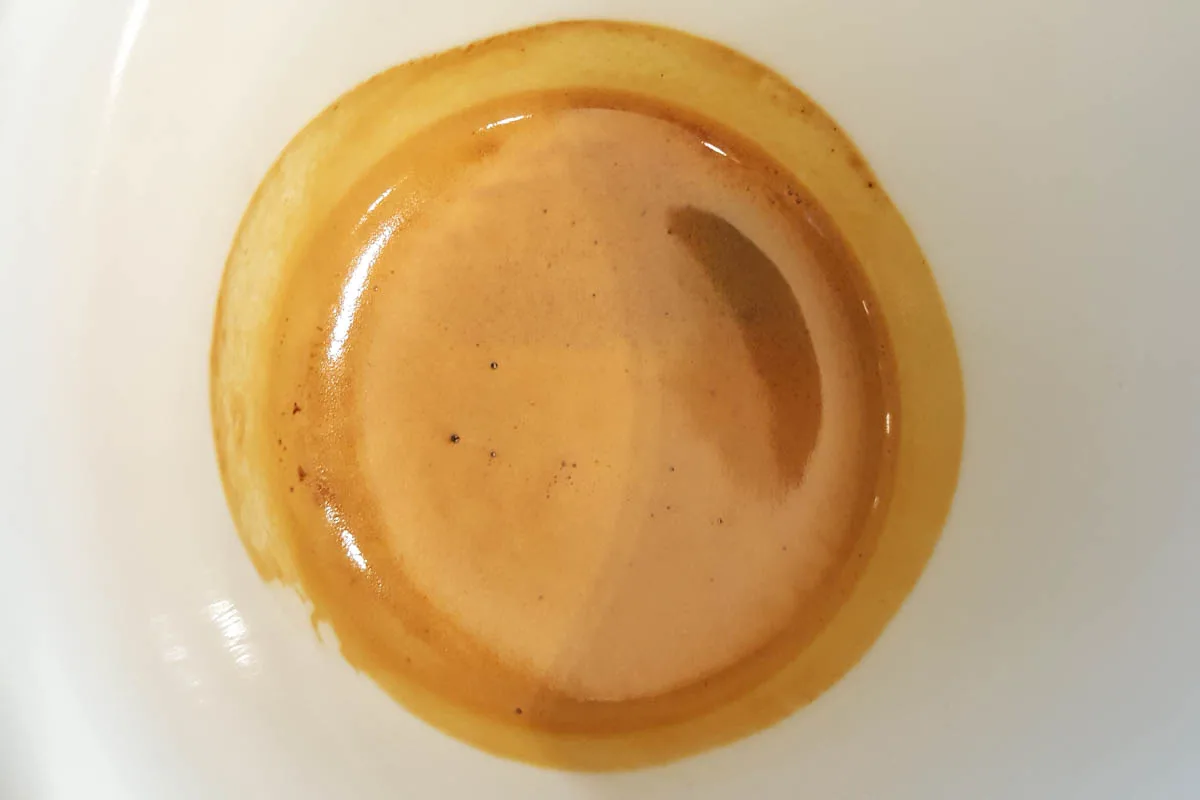

Achile Gaggia (1895-1961) – the inventor of the first modern steamless coffee machine. The main issue with the steam-operated coffee machines used until that moment was that they could burn the coffee making it taste bitter. Gaggia – at the time a barista in Milan – overcame that problem by using a revolutionary piston mechanism which allowed him to make an espresso in 15 seconds. In 1938 he patented his modifications. Due to the start of World War II, he couldn’t start producing his new machines. It was only in 1948 that Gaggia was able to found his company and turn it into an incredibly successful commercial enterprise. Unlike the old steam-powered machines, the Gaggia machines make espresso with crema. Crema is the natural layer of coffee oils which forms on top of the espresso thus giving it an intense and irresistible flavour.

Gio Ponti (1891-1979) – an architect, industrial designer, furniture designer, and artist among many other things. Inspired by the American cars and the jukebox, in 1947 Ponti designed one of the first horizontal coffee machines. Known as La Cornuta it was produced by the Pavoni company.

Coffee the Italian Way

The best way to drink coffee like an Italian is to have it standing at the counter in an Italian bar. You can do it while chatting animatedly with friends or while enjoying a peaceful moment completely by yourself.

If you are unsure how to proceed, spend some time just observing the locals at a local bar. You will see them walking in groups, in pairs or by themselves, giving their orders to the barista and then drinking their espressos in tiny sips before paying at the cash register and walking out.

The whole ritual doesn’t take longer than 6-7 mins in total.

A perfect cup of Italian coffee must satisfy what the Italians call the Quatro M del Caffe’ (the four M’s of coffee). These are:

- M for Miscela (blend) – the coffee blend used has an essential role.

- M for Macinadosatore (doser grinder) – this the machine which grinds the coffee beans and measures out the right weight of coffee grounds to make the perfect espresso. Ideally, this is 7 gr of coffee grounds. But that’s not all! It is also necessary to take in consideration how fine the coffee needs to be ground. For example, if the air is very humid, it is recommended to grind the coffee more coarsely and vice-versa. As such, the grinder needs to be adjusted daily or even several times a day to the weather conditions.

- M for Macchina per Espresso (espresso machine) – a complex machine that has undergone various developments and improvements over the last hundred years or so in order to serve you a perfect cup of Italian espresso every single time.

- M for Mano (hand) – the expert hand of the barista controls and fine tunes all the mechanical elements in order to produce the perfect cup of coffee. A good barista needs to know how to use and maintain as best as possible the different machines. He or she also needs to know the taste of his or her clientele so as to procure the right coffee blends and roasts.

In terms of roasting, traditionally Italians prefer coffees which have been roasted to a very dark brown colour. The coffee beans look shiny, a bit oily even as at the high temperatures at which they have been roasted, their essential oils have been released. The essential oils are fundamental for the coffee’s aroma which is composed by 800 different molecules. This type of dark roast renders itself well to the process of extraction through which espresso is made. The further south you go in Italy, the darker the roasts used become.

The dose for a perfect espresso is 7 gr. The pressure of the espresso machine should be between 15 and 18 atmospheres and the pressure of the water inside it – about 9 atmospheres. The temperature of the water should be between 88 and 95 degrees Celsius and the temperature of the espresso between 78 and 82 degrees Celsius straight from the machine.

Ideal extraction time is 30 sec (+/-5). The liquid in the small espresso cup should be 25-30 mil. The best way to taste the espresso is to serve it in a slightly flared at the top and warmed-up cup (35-40 degrees Celsius). If the machine doesn’t have a warming attachment, then hot water can be used. In order to enjoy an espresso at its best, it needs to be drunk at a temperature of about 60 degrees, not more than 2 minutes after being made.

When drinking espresso at a bar or serving coffee at home, Italians observe the so-called galateo del caffe’. This is their coffee etiquette according to which you need to use nice china cups with plates, to pre-heat the cups and to pour coffee until about two-thirds of the cup is filled.

Before sipping your espresso, it’s advised to have a small glass of water to clear up your palate. Sometimes, Italian bars keep this tradition alive by serving you a tiny glass of water for free with your espresso. More often than not though you have to ask for water and pay for it.

Even if you don’t add sugar to your coffee, you still need to mix it. This is done by moving lightly the spoon from top to bottom taking care not to touch the walls of the cup. This is the only way to distribute well the blend’s aroma and flavour. The cup is brought to the lips with the thum and the index finger of the right hand, while the left hand holds the plate. Spoons need to be for coffee and not for tea as coffee spoons are smaller. A slice of cake or a small dessert is also offered to the guests.

A large coffee vending machine takes pride of place in every Italian office, establishment, and even school. Offering at least ten different types of coffee – from a short and long espresso to a drink made of coffee mixed with hot chocolate – the machine is coin-operated and is the Italian counterpart of the British office water-cooler. A coffee drink purchased from a machine can cost as little as half an euro or so. The quality is generally quite good.

Types of Italian Coffees

There are many types of coffee drinks you can have in Italy.

Espresso (and not expresso) is the most well-known one. If you are in the Northern Italian region of the Veneto, instead of ordering an espresso, you can ask for a caffe liscio. You will get a shot of espresso but you will appear very local. If you want your espresso with a bit more water than usual, ask for a lungo. For an intense and condensed espresso, ask for a ristretto instead.

Cappuccino, Americano, and macchiato are what it says on the tin. However, in Italy there are no different cup sizes, so a cappuccino is served in what a British visitor of a multinational coffee shop may describe as a modestly sized cup. Americano in Italy, on the other hand, is served in two parts – an espresso and a small jug with hot water so that you can add as much as you want.

If you want a small cappuccino with less milk, ask for a macchiatone. A corretto is an espresso with a shot of liquor (usually grappa if you are in the Veneto in the North of Italy). A marocchino is an espresso with a layer of frothed milk dusted with cocoa).

If you want a latte (and you are not in a fancy coffee shop at Venice or Bergamo airport) then order a caffe latte otherwise you may be served just the milk in a glass.

My personal favourite here is a caffe con panna. This is an espresso with a huge dollop of freshly whipped cream. Yum! Although, not every bar would have the freshly whipped variety so it’s sbest to ask first in case you are served cream from a can. I have found that pasticcerie (that’s Italian for patisseries) are the best places to order this type of coffee in Italy.

Then there are coffees in Italy that masquerade as coffees but actually are not. For example, caffe al ginseng – a nutty and sweet hot drink prepared with ginseng extract mixed with coffee. Or caffe d’orzo – which is coffee-like drink made of barley. You can ask to have your cappuccino or macchiatone prepared with either ginseng or barley if you so wish.

To make things even more exciting, in summer Italians drink several cold coffee-based drinks. For example, caffè shakerato, caffè affogato, and my personal favourite – crema al caffè . To learn more about them, please, click here:

Coffee and Italy’s Economy

Coffee reenergises daily not just the Italians but Italy’s economy, too. According to data released in the last five years by the Italian Federation of Public Establishments (FIPE), the business of coffee here has a combined value in the region of several billion euros. From roasting and retailing coffee to manufacturing coffee making machines for home, office, and bar use, coffee is everywhere in Italy with thousands of people employed in the coffee sector.

Italy is also one of the world’s largest importers of coffee beans. There are 700 coffee-roasting businesses here. About one-third of the coffee roasted in Italy is then blended and packaged here and exported worldwide with Austria, France, USA, Australia, and Germany among the main clients.

As of 2018, Italians drink on average 2.2 coffees a day which equals 6 kg per head a year. All in all, 97% of the adult Italians drink coffee daily!

There are 149,000 bars in Italy – a bar here being a commercial place where coffee and other drinks are served. Each bar in Italy goes through 1.2 kg of coffee a day to prepare on average 175 coffee-based drinks. The most popular ones being espresso and cappuccino. This represents about one-third of the daily turnover of a bar of medium size.

Espresso in Italy doesn’t cost the earth. With a bar price of usually 1.00-1.30 euros for a freshly extracted cup, it is a pleasure that hundreds of thousands of Italians indulge in on a daily basis. Vending machines in offices, hospitals, factories, sports clubs, and even schools sell coffee at a much cheaper price – usually from 0.40 up to 0.60 euros per cup for a large selection of coffee-based drinks with or without sugar, with or without caffeine, with added hot chocolate, etc.

Barista is a popular profession in Italy with over 400,000 people working in bars making hundreds of coffees on a daily basis.

Having a proper Italian coffee is one of the most sought-after experiences for tourists in Italy with cappuccino being the coffee-based drink most ordered by them.

At home, Italians try to replicate the quality of bar espresso machines and invest in refined coffee-making machines with many different functions. The popularity of coffee capsules grows with every year. An ever-expanding range of coffees is now sold in capsules – from espresso to macchiato and mocaccino.

Coffee and Italian Cuisine

Coffee is not just a beloved hot drink in Italy. It also has found its place in Italian cuisine.

The most obvious example is tiramisu – one of the most famous Italian desserts in the world is prepared with coffee. From gelato and cakes to yogurt, coffee is widely used as a flavour in Italian patisserie. There is even a coffee-flavoured slush puppy in Italy. Just, make sure that you use its Italian name – granita al caffe’ – when you order it.

A particularly nice way to round off an Italian meal is to order an affogato al caffe’. This is a generous scoop of gelato on top of which a cup of freshly prepared espresso is poured.

In 1891, the Italian writer and food connoisseur Pellegrino Artusi dedicated to the coffee a memorable page in his famous cookbook Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiar Bene (Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well). In it, Artusi described how to prepare good coffee, retold the story of coffee, listed its different uses, mentioned coffee’s different qualities – from digestive to stimulating, gave suggestions how to choose coffee beans, as well as how to toast them, mix them and measure them in order to obtain the most appreciated blends.

On page 259 of his book, Artusi wrote: ‘This precious drink that spreads a great deal of excitement throughout the body was called the intellectual drink, the friend of writers, scientists and poets because, jolting the nerves, it brightens the ideas, it makes imagination more alive and thought more rapid.’

Italian Historical Coffee Houses

Elegant coffee houses have been the preserve of Italy since the 17th century. Initially considered to be a ‘place of perdition’ for serving as meeting points for lovers and a stage for shady dealings, coffee houses grew to enjoy a reputation as a place where elegant ladies and gents would congregate to discuss the matters of the day and where intellectuals could meet like-minded souls for a discussion on art, politics, and literature.

Here is a short list of some of Italy’s oldest and most famous coffee houses which exist to this day. Turin, Venice, Triest, Naples, and Florence are particularly famous as centuries-old centres of the Italian coffee culture. Yet, any Italian city you find yourself in is bound to have at least one very old and respected coffee house, so don’t miss a chance to find a local gem which is not included in this list.

Caffe Florian, Venice – founded on 29th December 1720 by Valentino Floriano Francesconi. This is the oldest cafe in Italy and the second oldest in the world in continuous operation. It was originally called Venezia Trionfante (Triumphant Venice) before taking on the name of its founder – Floriano – but dropping the final ‘o’ in the Venetian fashion. Make sure that you order a caffe’ alla veneziana – a Venetian coffee made of espresso with a dash of Florian liquor and topped with whipped cream.

Caffe Pasticceria Gilli, Florence – founded in 1733. This is the oldest coffee house in Florence. It opened its door when the city was still ruled by the Medici family! Renowned for its pastries and cakes, Gilli is the perfect prototype for the literary coffee house as through its existence it has attracted Italy’s most renowned writers, artists, and intellectuals.

Caffe Fiorio, Turin – founded in 1780. A historic coffee house which has conserved Turin’s atmosphere and traditions. This is also where you can taste the traditional for Turin bicerin – a hot drink made of espresso, drinking chocolate, and whole milk.

Caffe Bontadi, Rovereto – founded in 1790 as a coffee-roasting business, nowadays it still roasts coffee as well as having its own historical coffee house, a coffee museum and a barista academy.

Caffe Cova, Milan – founded in 1817 by Antonio Cova, this historical coffee house is a few steps away from Milan’s iconic Duomo. Doubling as a pasticceria, it’s the right place to head to in order to experience an excellent cup of coffee with a refined traditional dessert. According to the legend, the founder Antonio – once a soldier of Napoleon Bonaparte – was also the inventor of first panettone, which was named after him – Pan del Toni (Toni’s bread).

Caffe Pedrocchi, Padua – founded in 1831. Used to be known as the ‘cafe without doors’ as, originally, it was open 24/7. Caffe Pedrocchi houses a museum, too! On its piano nobile you will find the Museum of Risorgimento and the Contemporary Age. It documents the events of a tumultuous century and a half – from the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797 to 1st January 1948 (the day on which the Italian Constitution came into force)

Caffe degli Specchi, Triest – founded in 1839, it has hosted such illustrious personalities as Franz Kafka and James Joyce.

Gran Caffe Gambrinus, Naples – founded in 1860. A stunning belle-epoque coffee house which has also served as a creative hub for renowned intellectuals, artists and journalists.

Coffee Museums in Italy

The best way to learn in depth about coffee and its centuries-old relationship with Italy is to visit a coffee museum here. Have a look at this alphabetical shortlist. It will come in handy in your exploration of the traditions and history of coffee in Italy. Please, make sure that you check the websites of the respective museums before you visit as some of them are open only for groups and/or upon prior reservation:

Bontadi’s Coffee Museum is just up the street from the premises of the historic Bontadi Caffe in Rovereto, Trentino. There you can see a large collection of coffee-making machines, coffee cups, and anything and everything old and modern in relation to the art of making and enjoying a cup of coffee the proper Italian way.

Collezione Caffe’ Cagliari has one of the world’s largest and most complete exhibitions of bar espresso machines. You will find it in the city of Modena in the Northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna.

Dersut Coffee Museum also deserves the attention of all coffee-lovers. Dersut is Italy’s own chain of coffee shops. You will find its branches all over the country. The company’s Coffee Museum is housed in a historic industrial building in the charming medieval town of Conegliano in the Northern Italian region of the Veneto.

Enrico Maltoni’s Collection of Espresso Coffee Machines explores the history, culture, and design of espresso coffee machines. Organises temporary exhibitions and also has a large permanent exhibition in MUMAC (see below).

MUMAC is a museum dedicated to the coffee machine. In addition to the hundreds of espresso machines that the museum has, it also holds one of the largest collections of documents on coffee in the world. You will find MUMAC in Milan.

Museo Lavazza is in Turin in the North of Italy and gives you a chance to immerse yourself in the world of Lavazza – one of the most recognisable brand names in the world of coffee.

Omkafe’s Museo del Caffe’ is in Arco, Trentino. Visit it for an exciting journey through the history of coffee and its production. Among many coffee-related items and documents there, you can also see samples of more than 200 coffees from all over the world.

Coffee in Italian Art

With its wide reach, coffee in Italy has also left its imprint on Italian art. Here is a nice and tidy shortlist of some of the most famous works of art which feature a coffee cup, a coffee pot or a moment of daily life revolving around coffee.

I have tried to link each entry below to the respective work of art. You just need to click on each link to see how well coffee has lent itself to the brush of Italian painters.

In no particular order, here are some memorable coffee scenes in Italian art as well as the gallery or the museum where they are currently kept:

- Il Baciamano, Pietro Longhi – Pinacoteca dell’Accademia Carrara, Bergamo – the lady who is central in the painting’s composition holds a cup of coffee with her hand. A small tray with a coffee pot and a sugar bowl is placed on the table.

- The painter Francesco Guardi selling his paintings, Giuseppe Bertini – Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Milan – you will notice that the scene is set in a coffee shop on St. Mark’s Square in Venice. Coffee cups and pots are clearly visible on the depicted tables.

- At the coffee shop (Al caffe’), Alessandro Milesi – Frugone Collections, Genoa – an iconic painting of a young woman who is drinking a coffee while holding a daily newspaper.

- The Cup of Coffee (La tazza di caffe’), Mario Tozzi – a portrait of a pensive woman sitting at a table with two cups of coffee.

- Woman at the Cafe (Donna al caffe’), Antonio Donghi – Ca’ Pesaro, Venice – a portrait of a lone woman at a cafe table.

- The frescoes by Michelangelo Morlaiter in Palazzo Grassi in Venice shows coffee, biscuits, sweets, and colourful sorbets being served to noble ladies and gentlemen.

- The frescoes by Francesco Zugno in the foyer of Teatro Grande in Brescia show coffee being served to a noble gentleman.

In addition to Italian art, coffee features heavily in many marketing and advertising campaigns which have become legendary in Italy. An artist called Leonetto Cappiello has drawn some of the most recognisable coffee marketing posters and campaigns here. Among them is the poster with the man in a yellow coat hanging from the door of a fast train while a cup of espresso is expressly made by a silvery Victoria Arduino machine.

Coffee Terminology in Italian (Both Antiquated and Modern)

Acquacedrataio – a term used until the end of the 18th century in Florence. It meant a street seller of coffee, hot chocolate, and other refreshing drinks. It was then replaced by the term caffetiere.

Bar – an anglicism which is widely used in Italy and it has come to signify a commercial place where coffee and other drinks are served and are taken predominantly standing up in front of the counter.

Barista – a term created during the period of Italianisation so as to abolish the anglicism ‘barman’. Nowadays, barista is a term used all over the world to specifically describe a person working in a coffee shop and explicitly having the responsibility of making a large variety of coffees. In Italy, the distinction is not so clear cut and you can also often hear the terms ‘barman’ and ‘bartender’ being used.

Bottega del caffe’ – the original coffee shop. Bottega in Italian means a small shop or workshop where a small business conducts its activities. Initially, coffee shops in Italy were called bottega del caffe’. Nowadays, they are called bar, caffe’ or pasticceria. A bar will serve all sorts of coffee-based drinks alongside pastries, light snacks and alcoholic beverages. A caffe’ may also serve light meals. A pasticceria is where you get a large variety of cakes and bakes in addition to all types of coffee and soft drinks.

Caffe’ sospeso – Mainly typical for Naples, this is the tradition of paying it forward in terms of coffee. In a nutshell, people pre-pay a spare coffee when they buy one for themselves. This way, someone who doesn’t have the means, can treat him- or herself to a nice coffee when they need a little pick-me-up.

Caffetiera Napoletana or just Napoletana (also known as cuccumella)- a type of flip coffeepot used in Naples. It is believed that it was invented in 1819 by a Frenchman called J.L. Morize. The Napoletana consists of two cylindrical pots (called cucccma and capello), divided by a basket filter for the finely ground dark roast coffee. The top pot has a spout. The water is poured in the bottom pot. The caffetiera napoletana is placed on the stove and when the water starts boiling, it is removed from the fire. The coffeepot is then turned upside down so that the hot water can filter through the coffee grounds. After three minutes the coffee is ready to be poured.

Caffetiere – traditionally, manager of a bottega di caffe’. The term was used by the Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni in the mid-18th-century.

Espresso – originally a coffee made with a steam machine. Nowadays, it mainly means a strong coffee made with an Italian bar espresso machine.

Galateo del caffe’ – the Italian coffee etiquette or in other words the set of rules which Italians follow when serving and/or drinking a coffee at the bar, the restaurant or at home.

Moka or Moka Express – a traditional coffee pot invented and patented by Alfonso Bialetti in 1933. Millions of Italians use a Moka coffeepot every day to prepare a coffee at home. It consists of two parts and a small filter for the coffee grounds.

Ponce – from ‘punch’ in English, ponce is a coffee-based drink enjoyed in the city of Livorno, Tuscany. It is prepared with sugar, lemon peel, rum (which can be mixed with cognac or sassolino – an alcoholic drink from the province of Modena), and espresso ristretto.

More Helpful Links

- Italian Espresso National Institute

- International Institute of Coffee Tasters

- Milano Coffee Festival

- Comitato Italiano del Caffe’

- A History of Espresso in Italy and the World by Jonathan Morris

- The Curious Story of How Transatlantic Exchange Shaped Italy’s Illustrious Coffee Culture by Cosimo Bizzarri

- Illy Universita del Caffe

In Conclusion

Coffee and Italy are indeed a match made in heaven. Over the last four centuries, coffee culture has found fertile ground in Italy and so much what we, nowadays, take for granted about coffee, was originally invented, tested, and improved here.

From the first merchants reaching Venice with bags of coffee beans from the Egyptian ports and the first coffee houses opening their doors around the Italian cities to the first espresso machines to be used at home and at work, coffee and its traditions have flourished here.

My blog post above takes you a journey through the multifaceted relationship of coffee and Italy. From a historical overview to helpful lists with Italian coffee museums and historical coffee houses, from coffee in Italian art and Italian cuisine to mentions of coffee in Italian written works, every possible angle is covered.

I hope you enjoyed discovering new things about your, likely, favourite (or, at least, habitual) drink.

Are you a coffee fan? Which is your favourite type of coffee? Where in the world did you have the best coffee ever? And, I know it’s a lot of questions, but I am curious to find out: which has been the most memorable coffee shop you have ever been to?

Let me know if the Comments section below. Thank you!

Thank you for reading! Please, leave me a comment, pin the image below or use the buttons right at the top and at the end of this blog post to share it on social media.

For more useful information like this, please, like my blog’s page on Facebook and subscribe to my weekly strictly no-spam newsletter.

audreychou

Wednesday 7th of April 2021

Hey Rossi! Thank you so much for such a detailed and informative article! I thoroughly enjoyed it! I'm particularly interested in what you said about "Buying a lady a cup of coffee and having it sent to her table was a way to express one’s love and devotion to her." I wanted to learn more about this and looked it up, but unfortunately I can't find anything. Would you mind sharing more details about this? Thank you so much!

admin

Wednesday 7th of April 2021

Thank you for your comment and your kind words. In reply to your query - I don't think there will be any information about this in English. I found this curious detail during my research on coffee and its traditions in a specialised food library in Italy (Biblioteca La Vigna, Vicenza). As I don't live in Italy anymore and as my notes from that period were one of the many things we couldn't transport back to England, I don't recall the exact name of the source. Hopefully, in future, I will have a chance to do more research at La Vigna again. Best wishes,

Rossi

Daniele Fasoli

Wednesday 6th of January 2021

Great article Rossi! Thanks for sharing.

I was writing an article about Italian Coffee Types and I found your post: such a great source for deeping the argument. I am definitely linking to you :)

admin

Wednesday 6th of January 2021

Thank you, Daniele! I appreciate it coming from an Italian. :) Have a lovely day and I enjoyed reading through your blog.

Best wishes,

Rossi :)

Joanna Lucarino

Tuesday 1st of September 2020

This was so interesting!! Thank you so much for inspiring me to write a short article (difficult to make it short) on the culture of coffee in italy for a local italian newspaper!!

admin

Tuesday 1st of September 2020

Thank you for your kind words! Good luck with writing the article. I hope you use the information here as inspiration only. Please, refer to the Copyright Notice at the bottom of this page for more information on this. Best wishes,

Rossi :)

Roberto

Monday 31st of August 2020

Well done and well written, and quite comprehensive. I could not think of anything else that should be added (or neglected).

admin

Tuesday 1st of September 2020

Thank you! I appreciate your kind words. Best wishes,

Rossi :)

Ayse

Saturday 25th of July 2020

Hello Rossi. Thank you so much for this profoundly informative article. As a coffee lover I enjoyed especially the history part, the journey of coffee from Yemen to Italy. Regards from London Ayse

admin

Friday 7th of August 2020

Thank you, Ayse! About Yemen and it being the homeland of coffee: I read a very interesting book recently - The Monk of Mokha. It painted a vivid picture of the history of coffee and its Yemeni roots. Best wishes,

Rossi :)