A week ago I found myself in a 13th century church in Padua. Called Chiesa degli Eremitani or the Church of the Hermits, in English it is actually known with the bilingual name the Church of the Eremitani. It is one of the most well-known sights in this Northern Italian city as the annexed to it former monastery nowadays serves as the municipal art gallery.

I was in Padua on an improvised short trip. It was one of those days, drizzly and grey, when Vicenza felt a bit too tight around my neck and, free of any obligations for most of the morning and the whole of the afternoon, I jumped on the first train to leave the station after my hurried arrival at it. As luck would have it, 17 minutes later I was in Padua with no specific plan of action.

I decided to walk around the city centre (a place I had already visited several times before) and just take it all in and then pop into any historical or religious building which was open for visits and which (I felt) pulled me inexplicably to itself. This is how I came across the Church of the Eremitani, slightly tucked away from the city’s main thoroughfare, yet central enough that you couldn’t miss it if you really wanted to go there.

An information panel just outside of the church caught my eye. It recounted a few intriguing details about the medieval Bakers and the Bread-Sellers’ Guild, the members of which used to meet at the Altar of Saint Ursula – protectress against fire – in the church centuries ago. My curiosity was tickled by such whimsical details like the fact that the guild was one of only two in Padua of yore to accept women as members. Wanting to find out more, I pushed the heavy and tall wooden door and walked inside the silent church.

I was staggered by its size. A long, straight nave stretched for dozens of meters right ahead of me and straight above my head. It was crowned by the most impressive vaulted ceiling. Made of uniform wooden beams it looked like the upturned hull of a very large ship.

Save for a man who was quietly praying, the church was empty. It didn’t feel intimidating though. Its tall structure seemed to soar up towards the sky, making me feel peaceful and at ease inside.

Looking around I was surprised to see how bare this otherwise impressively big church was.

Used to religious buildings’ walls generously covered in rich frescoes, I found Padua’s Church of the Eremitani rather ascetic in this respect. There were two marble sarcophagi on both sides of the entrance, a 14th century Madonna with the child Jesus surrounded by saints and outlined with intricate stone rims, some old and very faded frescoes, and a mausoleum with marble statues. Then a big clock painted directly on the mortar a little bit further away.

Otherwise, the big walls stood bare save for their pattern of long parallel bands in pale ochre and pale red.

On the right-hand side of the nave stood the entrances to several small chapels. Inside of them candles were still ablaze with the prayers of the people who had placed them there in the minutes prior to my walking in.

Fragments of faded frescoes were adorning these little chapels, too. I stood for a little bit there, inside one or two of them, looking at the images, or what was left of them, on the walls. The hands of time had erased the brightness of the original colours, they had smudged away the frescoes’ original shapes.

I continued towards the altar of the church. In the low light I could see that the left-hand wall of the central apse, in which the altar was placed, was covered in frescoes from the ground all the way up. Yet the central and the right-hand walls were bare, save for a big crucifix and two small paintings.

The central apse was bordered by two more, each lateral apse (or chapel) being half the size of the central one. Something about the right-hand apse caught my eye, made me step away from the centre and go straight to it.

And then I glimpsed a most curious sight.

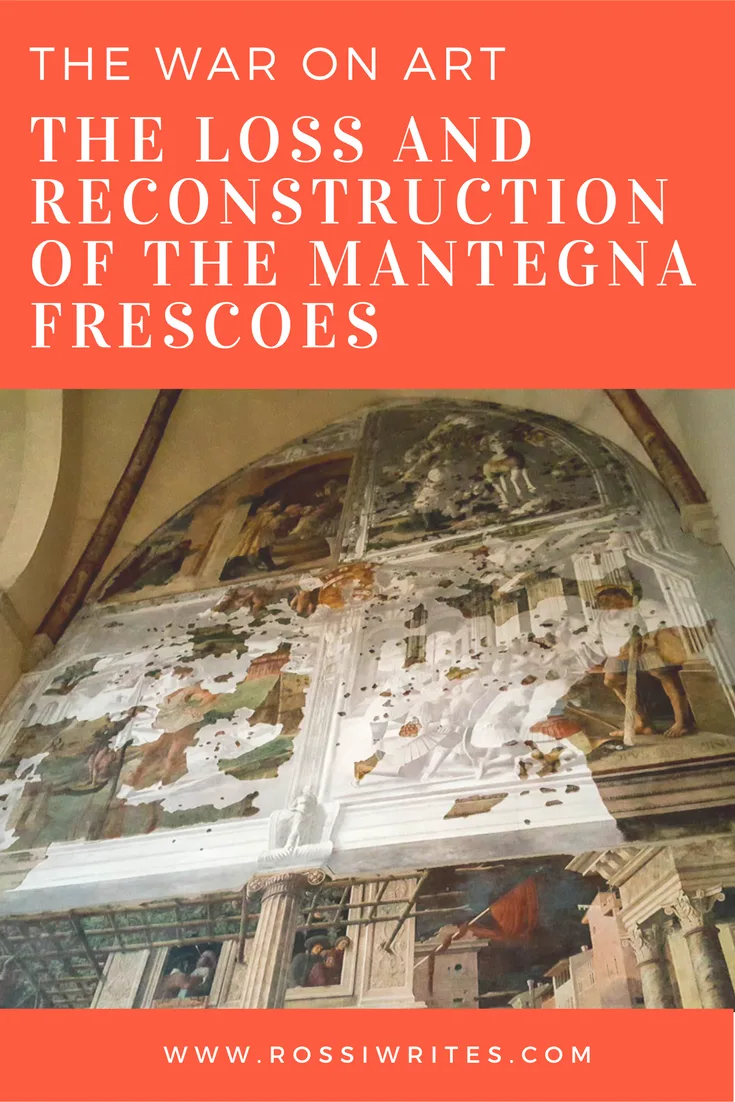

The right-hand apse was also covered in frescoes, but they looked a bit odd. They were like big black and white panels on top of which tiny pieces in full colour were placed. It was like a huge unfinished puzzle with some very irregular jagged bits.

Here and there the puzzle seemed almost complete – bursting in beautiful bright colours and showing masterfully painted and almost sculptural in their aesthetics scenes. Other panels were mostly entirely back and white with just some minuscule portions of colour added to them in a seemingly random way.

What was that!?

The answer was provided by a small series of informational posters attached to the opposite wall. It all made sense and, at the same time, it was difficult to grasp.

These fragmented frescoes were the work of the 15th century Italian painter Andrea Mantegna whose paintings nowadays grace such worldwide renown museums like the Louvre in Paris and the National Gallery in London. He also happened to be the brother-in-law of a favourite painter of mine – Giovanni Bellini. Apparently, in his work Mantegna experimented with lowering the horizon to achieve a monumental effect and his figures look almost like carved out of stone.

Curious tidbits aside, the important thing was that in 1448 Mantegna (alongside some other fellow painters) was commissioned to decorate the Ovetari Chapel in the right-hand apse in the Church of the Eremetani. The work started and stopped several times over the nine years that it lasted. The painters disagreed and fell out with each other. Some of them passed away, leaving behind unfinished portions of the frescoed walls.

Hence between 1453 and 1457 Mantegna took it upon himself to finish the Ovetari Chapel. He entirely created the cycle of frescoes on the Stories of St. James on the left-hand side, painted the Assumption of the Virgin on the central wall and finished the lower sector of the cycle on the Stories of St. Christopher on the right-hand side of the chapel.

For a painter in his mid-twenties, the resulting frescoes were a remarkable achievement. In their execution Mantegna had to overcome difficult technical problems. For example, considering the tremendous height of the chapel, he had to consider the low viewpoint which people in the church would have and thus adapt his perspective accordingly.

The frescoes became one of the important pieces of Italy’s rich artistic heritage.

And, then, almost 500 years after they had been painted, they were destroyed. By a bomb.

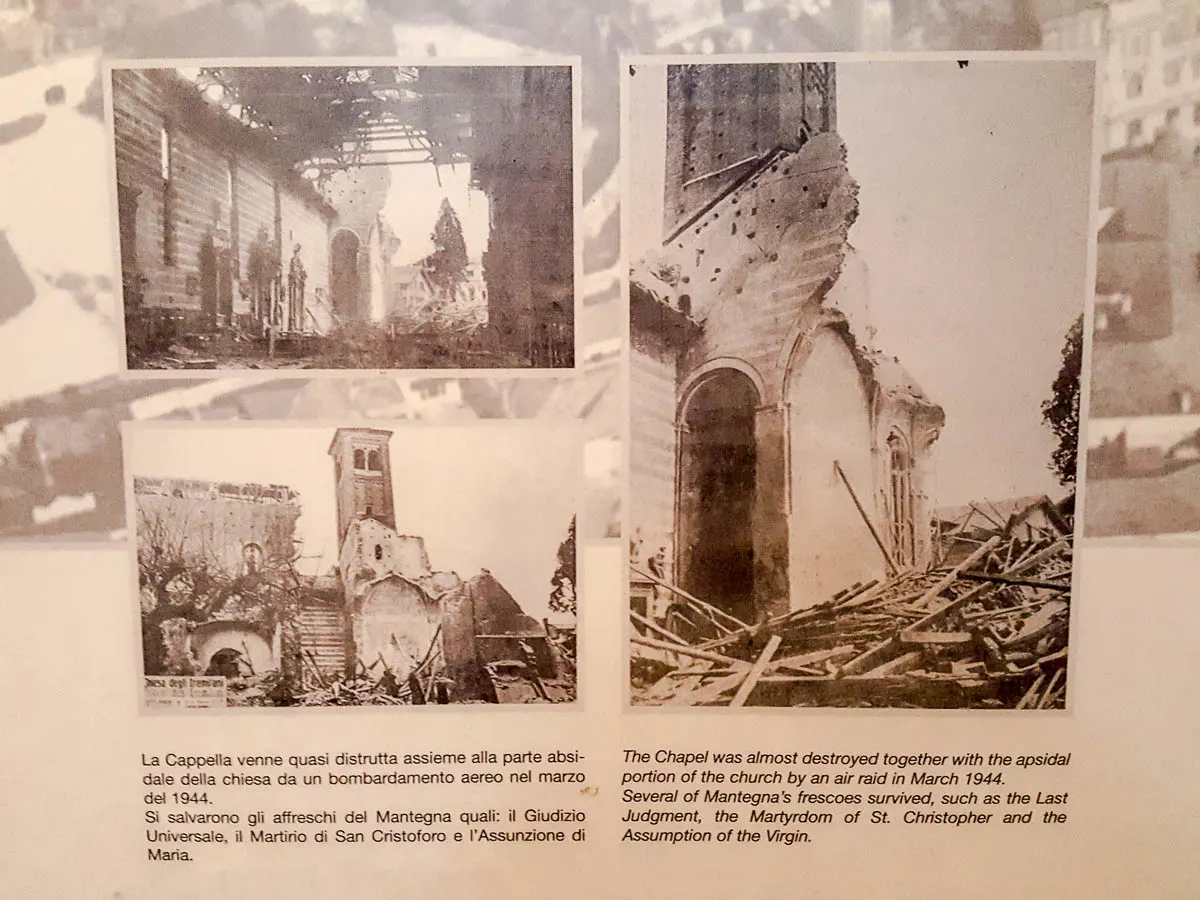

On 11th March 1944 the Allied Forces bombarded the Church of the Eremitani and in the process they almost completely destroyed the Ovetari Chapel. The bombardment was aimed at the nearby German barracks. Still, the church and its frescoes became a collateral damage in the war.

Mantegna’s frescoes fell to pieces on to the ground. What once were a priceless work of art admired by Goethe himself, was reduced to rubble. Over 88 thousand fragments of the Stories of St. James and St. Christopher mixed with the fragments of plaster and bricks of the destroyed chapel walls.

On that day art died.

With all the works of art in the world, with the different aesthetics and spiritual needs which have conditioned their inception, have you ever stopped to think about the art humanity has lost?

All those church frescoes that are no more, all those statues which have been destroyed, all those paintings that have been thorn?! Often this was caused by the simple and natural passage of time – its cruel hands chipping away at perfectly proportioned marble limbs and reducing formerly bright as the sun colours to murky shadows. Other times, this was due to lack of resources – maintaining art at its best costs a lot without promising immediate financial returns, so sometimes the need to maintain and restore works of art is simply ignored.

More often than not though the art around us is destroyed by us. People at war – with another religion, with another nation, with another way of thinking and life. For there is no other way to subjugate the soul of the enemy than to destroy what he considers to be creative and beautiful. The most important thing that wars destroy in us is the sense of beauty – beautiful buildings fall to the ground, beautiful art is left to burn or is attacked with hammers and bombs.

And even though our consumption of art is the most ephemeral of all our consumption needs, it is also the most important one of them all. We consume water and food to feed the body and give it strength. The matter of the food we eat and the water we drink transforms into the matter of our bodies – we feel our muscles tense, we feel our faces smile, we feel our whole body’s pain.

What art feeds though is beyond that – it takes care of our soul. It gives us visual delight, it raises questions in our heads, for a fleeting moment it makes us see that the world is beautiful in spite of all its ugly day-to-day banalities. Looking at a statue, admiring a painting, walking into a gallery to feast our eyes on its collection, going to a former palace to see its painted ceiling, lifting our gaze up as we walk past a stunning building – all of these are ways to remind ourselves of the creative force we carry within us, all of these are little moments when we experience a connection with the artist and through his work – with all the other people who have admired it or questioned it before us.

Apparently, worried about the preservation of Italy’s artistic heritage, the authorities of Padua had given the Allied Forces a list with all the buildings in the city which were not to be attacked. This didn’t save the Church of the Eremitani, even though it featured on the list. Its position next to the German barracks sealed its fate. And one attack on the enemy became an attack on art. Collaterally, yes. Still…

There are two good things in this story. One was that back in 1880 some of Mantegna’s frescoes had been removed from the church to save them from the damp walls. These were the two lower panels of the Stories of St. Christopher and the whole Assumption of the Virgin on the central wall. Thus, unwittingly, they were saved from the bombs in the Second World War.

The other good thing is that those tiny 88 thousand fragments into which the rest of the frescoes collapsed, were picked from the rubble and preserved. For many years they were stored in crates in an archive in Rome and then in 1992 they were cleaned, photographed and sorted. In 2000 the Project Mantegna was set up aiming to reconstruct the frescoes based on black and white photographs taken of them between 1900 and 1920.

A special piece of software was developed aiming to achieve the unachievable – define as precisely as possible the probable place of each fragment in the original frescoes.

This is what I had seen in the Ovetari Chapel in the church. Those black and white panels with the colourful fragments positioned on top of them were the result of the extremely labourious, time-consuming endeavour to rebuild a lost piece of art. Work was completed in 2006 and even though the recovered fragments constituted only about one-tenth of the surface of the original frescoes, the result is staggering.

For we can feel right there and then the fragility of art, the destruction of war and how our souls and minds are caught intermittently between them both.

P.S. If you find yourself in Padua, please, make sure that you visit the Church of the Eremitani. The church itself is very interesting with its story, architecture and frescoes by Andrea Mantegna and other painters. You can see the reconstructed Mantegna frescoes in the Ovetari Chapel there, too. There are some simple informational posters about the Mantegna Project on the wall. The story of the frescoes – their loss and their reconstruction – is very powerful and it deserves to be told over and over again .

What do you think? Will we ever be able to find a balance between what our souls and our minds need and want? Do you know of any other works of art which have been lost due to acts of war? Has anything been done to bring them back to life?

If you liked what you read, please, leave me a comment or use the buttons below to share it on social media.

For more stories like this you can follow me on Facebook and subscribe to my weekly strictly no-spam newsletter. Thank you!

Ros

Thursday 26th of May 2022

I found this a very useful commentary and I share your love of the great Mantegna. I saw the restored fresco this morning and will pay another visit before I leave Padua. You also summarise the importance of art in very few words. Thank you.

admin

Thursday 26th of May 2022

Thank you for your very kind words! Have a wonderful time in Padua. Such a lovely city to visit in Italy!

Best wishes,

Rossi Thomson :)

Ron

Thursday 7th of February 2019

Thank you !

The German poet Goethe also visited in his “Italian Journey” (1786) Eremitani in Padua and saw Mantegna undestroyed:

“In the Church of the Eremitani I have seen pictures by Mantegna, one of the older painters, at which I am astonished. What a sharp, strict actuality is exhibited in these pictures! It is from this actuality, thoroughly true,—not apparent merely, and falsely effective, and appealing solely to the imagination,—but solid, pure, bright, elaborated, conscientious, delicate, and circumscribed; an actuality which had about it something severe, credulous, and laborious,—it is from this, I say, that the later painters proceeded (as I remarked in the pictures by Titian), in order that by the liveliness of their own genius, the energy of their nature, illumined at the same time by the mind of the predecessors, and exalted by their force, they might rise higher and higher, and, elevated above the earth, produce forms that were heavenly indeed, but still true. Thus was art developed after the barbarous period…”

Ron

Saturday 4th of August 2018

Thank you !

The famous poet Goethe visited in his "Italian Journey" (1786) Eremitani in Padua and saw Mantegna undestroyed:

"In the Church of the Eremitani I have seen pictures by Mantegna, one of the older painters, at which I am astonished. What a sharp, strict actuality is exhibited in these pictures! It is from this actuality, thoroughly true,—not apparent merely, and falsely effective, and appealing solely to the imagination,—but solid, pure, bright, elaborated, conscientious, delicate, and circumscribed; an actuality which had about it something severe, credulous, and laborious,—it is from this, I say, that the later painters proceeded (as I remarked in the pictures by Titian), in order that by the liveliness of their own genius, the energy of their nature, illumined at the same time by the mind of the predecessors, and exalted by their force, they might rise higher and higher, and, elevated above the earth, produce forms that were heavenly indeed, but still true. Thus was art developed after the barbarous period..."