‘To finish the pogača off, you brush it with beaten egg and then sprinkle it with cumin seeds and coarse salt.’

Bernarda’s hands moved fast showing us just what she meant. Her fingers generously coated the loaf with egg and then she scattered a helping of cumin seeds and salt crystals over the traditional Slovenian bread.

‘Now, 15 minutes in the oven and the pogača will be ready’. Bernarda rounded off the presentation and disappeared at the back of her shop where the hot oven was located. We waited eagerly anticipating the taste of the freshly baked pogača.

Pogača was the first traditional food we sampled during our summer visit to Slovenia – a beautiful and yet largely unspoiled by mass tourism European country. After a four-hour drive from our current hometown of Vicenza, Italy we reached Big Berry – a luxury glamping site – where in our mobile home a basket with a large piece of pogača was waiting to greet us at arrival.

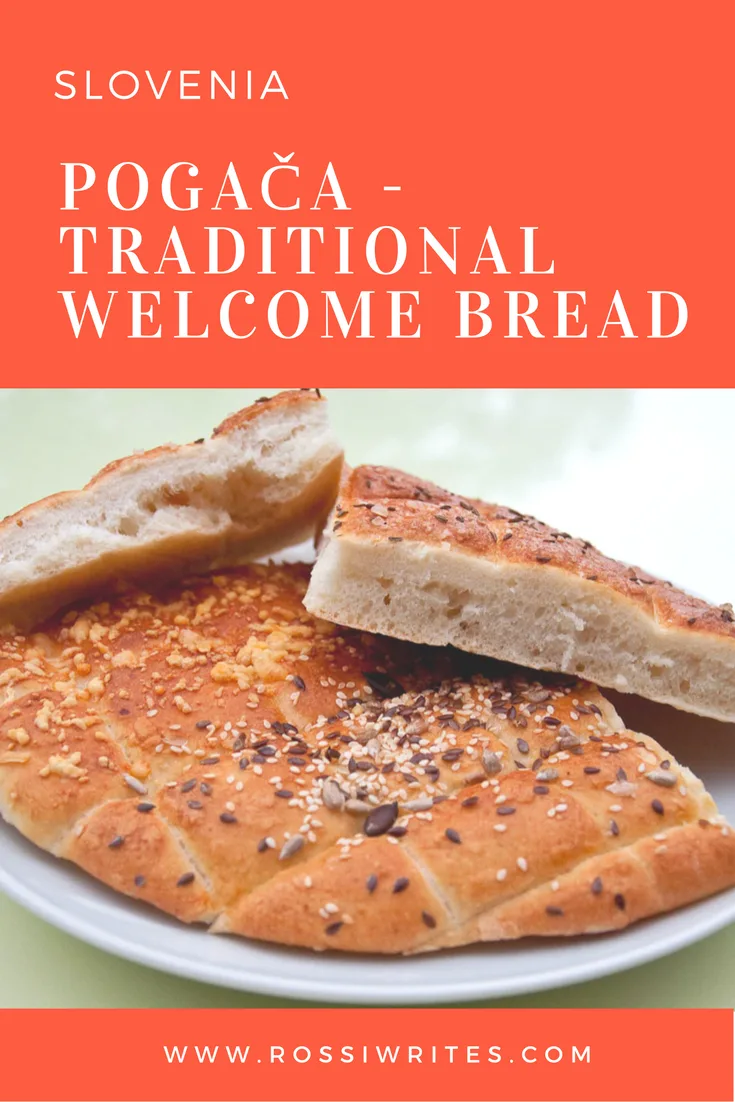

The salted loaf was soft and fragrant spiced with cumin and rosemary. Its grid-like surface made it easy to tear off large uniform chunks to greedily stuff in our mouths, hungry from the long uninterrupted drive.

‘What was that amazing flatbread you had left in the mobile home for us?’, later that evening I asked Ana Iskra – the glampsite’s marketing coordinator who took care of its guests.

‘Oh, this is Belokrajnska pogača‘, she replied. ‘Traditionally, guests in Slovenia are offered a freshly baked pogača to tear a piece off as a sign of being welcome into the the house of their hosts.’ The roots of the flatbread lie in the Slovenian region of Bela Krajina (also known as White Carniola in English) and its name – pogača – comes from the Latin term panis focacius meaning ‘bread baked on the hearth or fireplace’.

The Italian focaccia has the same etymology, yet Slovenia’s pogača is round and there are strict rules as to how to shape it.

I was familiar with the tradition of pogača, as in Bulgaria – where I am from – we also welcome guests with a large handmade loaf, called погача (pogacha) a piece of which is dipped in salt by the guest. What I was unfamiliar with though was the Slovenian version of it and how it was made. Unlike its Bulgarian counterpart, the Slovenian pogača was flat and thin – raising to about 3-4 cm in the centre and then sloping down to 1-2 cm at the edges. It also had this grid-like structure on top, due to incisions having been made with a knife in the dough right before baking.

On the following day we went for a walk to the nearby town of Črnomelj.

The town was in the midst of hosting Slovenia’s oldest folklore festival – Jurjevanje – and the streets were full with people in folk costumes from all over the world mingling with the locals. Črnomelj had an old-fashioned charm to it, like time had stopped and people lived quiet tranquil lives unspoiled by modern stress.

We watched the songs and dances on the large stage in the middle of town and then, hungry, we followed our noses to a small lovely shop – the home of a traditional bakery and handpicked local produce. A table laden with pretzels, fresh raspberries and lavender pouches was laid on the street right outside of its door and then we went up the two stone steps to have a look inside.

There we encountered Bernarda – the formidable owner of the shop and, as we were about to find out for ourselves, a veritable pogača master.

We chatted with her for a bit, quickly establishing a connection with this warm and welcoming lady.

‘I am going to show you how to make pogača‘, she said.

She brought out a small ball of dough made with flour, yeast, warm water, a bit of sugar and salt. The dough had been already left to rise for about 20-30 minutes.

Bernarda’s skillful hands spread out the dough into a flat disk of about 30-33 cm. Then she picked a large knife and carefully made deep incisions into the dough.

‘You need to be careful not to cut all the way through. Just deep enough,’ she explained.

The first incision was made in the centre right across the bread and then she cut the other lines parallel to it, leaving about 4 cm between them. Next Bernarda turned round the baking tray and cut the bread again in straight lines at a perfect right angle to the already made incisions.

The final step was to brush the pogača with beaten egg and generously sprinkle it with cumin and coarse crystals of salt.

Once the tray was in the oven, we counted the minutes to a fresh fragrant pogača.

If you find yourself in Slovenia, make sure that you try Belokrajnska pogača for yourself. You can contact Bernarda Kump at BIBI Turizem and on Facebook. You will find her lovely shop-cum-bakery on the high street in Črnomelj, Bela Krajina (White Carniola).

We were hosted by the brand new Big Berry Glampsite on the river Kolpa in Slovenia which is about four hours drive time away from Vicenza and offers seven mobile homes to experience the luxury of freedom. As usual, all opinions are entirely my own.

Have you been to Slovenia before? What was the best food you tasted there? Share with me your experiences in the ‘Comments’ section below. I would love to read them and engage with you.

For more stories like this, please, follow me on Facebook and subscribe to my weekly strictly no-spam newsletter. Thank you!