Moretta – a small oval mask made of black velvet – has always intrigued me. It was worn exclusively by women and it did not allow its wearer to speak, hence it was called ‘the mute mask’.

From our modern point of view about genders and relationships between men and wormen, the Moretta looks rather depersonalising and depressing. Yet, in its time it was nothing like this.

I have read lots about the Moretta, but have never actually seen it worn. The mask was popular in Venice back in the 16th and the 17th centuries, after which it stopped being used. And even with the revival of the Venetian Carnival nowadays, it seems, the Moretta never came back in vogue.

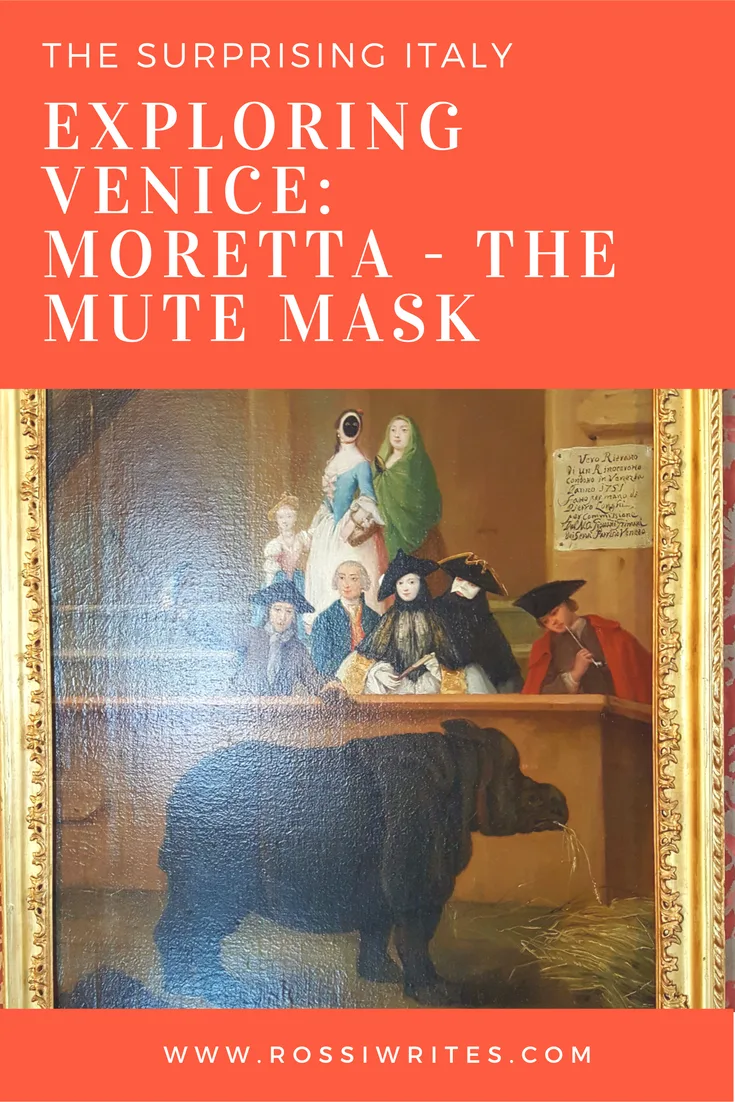

So, I was delighted when I came face to face with the painting pictured above during a visit to Venice yesterday. I was in Ca Rezzonico – a beautiful museum overlooking the Grand Canal. I walked into a room on its second floor to come across a huge selection of paintings by Pietro Longhi depicting detailed scenes of Venetian life.

It was like a window into a bygone world had been thrown open wide. Hung in two lines on two of the walls of the room, the paintings showed Venetians in every possible moment of their extravagant lives. I recognised ‘Clara The Rhinoceros’ straight away. It is a quite well-known painting with two versions of it and I had seen its other version (in which four of the men are masked) at the National Gallery in London some time ago. The subject matter is an Indian rhinoceros, named Clara, which was touring Europe and in January 1751 reached Venice which was in the throes of the Carnival.

Looking at the painting, what took me by surprise now though, was not the unusual appearance of the animal or the appalling fact that the man on the left holds its sawn-off horn. For the first time I actually focused on the women at the back and noticed that one of them wears a Moretta mask.

Wow!

You know that overwhelming feeling when you are in an art gallery and you end up seeing so many paintings that they all become one big blur. And then a little detail jumps out at you from somewhere and suddenly the world gets back in focus and you feel like your being there at that very moment enriched your life a little bit.

Well, seeing (or, actually, noticing) the Moretta-wearing woman in this painting for the first time was not really a life-changing event as such for me, but still it gave me an answer to a question which had played on my mind for a little while: what did actually the mask looked like when worn.

You see, with Carnival in Venice just around the corner (it starts on 11th February 2017) photos of people, dressed in lavish costumes and with faces concealed behind elaborate masks, have been flooding my social media feeds for the past couple of weeks. Shot against the dreamy backdrop of the city on water, they seem like something straight out of a fantastical, imaginary world where extravagance and unrestrained ornamentation win over comfort and practicality every single time.

I follow a lot of Venice-related pages and websites and this is the time of the year when everyone talks about Carnival, its origins and the historical meaning of the different masks. The more well-known of them are, obviously, the Plague Doctor (whose beak usually makes men wistfully laugh), the Bauta (the prominent, triangular chin of which brings up dark memories of ‘Eyes Wide Shut’) and the Colombina (the traditional half-face mask which both conceals its wearer’s identity and reveals his or her face in the best possible way).

Not to mention the huge variety of modernised masks which are sumptuously decorated with glitter, feathers, sparkly sequins, and ribbons in metallic colours.

Among this extravagance of colours, shapes and ornamental details, the plain, featureless Moretta is very rarely mentioned, if at all.

Made of black velvet, the mute mask is oval in shape with a prominent bulge to fit in the nose. It has round holes cut for the eyes and it covers the face from the middle of the forehead to just below the bottom lip and from the left temple to the right temple. There is no opening left for the mouth. This, per se, is not a unique thing, as for example the traditional Bauta mask also doesn’t have a mouth opening as such.

The thing though is that the person wearing a Bauta can still speak and the triangular shape of the bottom half of the mask serves as an acoustic chamber where his voice reverberates thus changing its tone and timbre, making the masked man even more difficult to recognise.

Unlike this, the wearer of the Moretta mask is not able to speak at all, as the mask is kept in place not by the traditional ribbons tied up at the back of the head, but by means of a button sewn on the level of the mouth on the inside of the mask, which the wearer would hold tight between her lips.

Hence the full name of this mask is the Moretta Muta – the Dark Mute Mask.

It is also called Servetta Muta, meaning ‘mute servant woman’, although in fact the mask was worn by wealthy patrician women. For all its depersonalising lack of voice and features, the Moretta was in fact a weapon of seduction. In Venice of the 16th and 17th centuries, women would wear it to create an aura of mysticism and to intrigue men.

As the ladies of Venice of three or four centuries ago had the freedom to wear revealing clothes emphasising their God-given gifts, the Moretta (originally inspired by a French mask, which had an opening for the mouth) became their secret weapon to attract the interest and to titillate the imagination where a bare shoulder or a low neckline would fail.

In order to be able to speak to a man, a Moretta wearer would have to remove the mask and in the process she would reveal her features and her identity, too. So, she would do this only if the man, who was trying to win her attention, was to her liking and she wanted to get to know him. As such the mask was used as a means of control giving the woman the right to choose.

It is an interesting fact to know, as from our current point of view, the Moretta, at a first glance, seems quite oppressive and a bit spooky, too. To be perfectly honest, I am quite happy that the mute mask fell into disuse and that today we don’t feel the need to hold a button between our lips and obscure our face so as to get some attention from a man. Still, the Moretta has an interesting story and connotations and I for one am always happy to learn as much details about Venice and life there through the centuries, as I can humanly can.

Have you been to the Carnival in Venice before? Which one is your favourite Venetian mask? What do you think of the Moretta Muta? Would you give it a try or do you find it a bit freaky after all?

If you liked what you read, please, leave me a comment or use the buttons below to share it on social media.

For more stories like this you can follow me on Facebook and subscribe to my weekly strictly no-spam newsletter. Thank you!